Flat Affect

Flat Affect

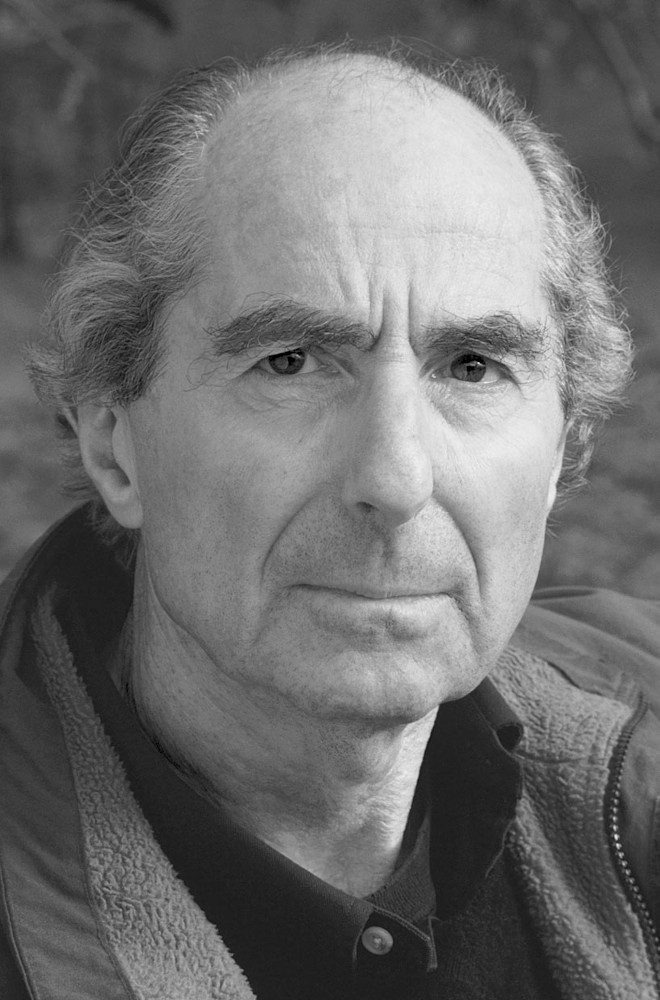

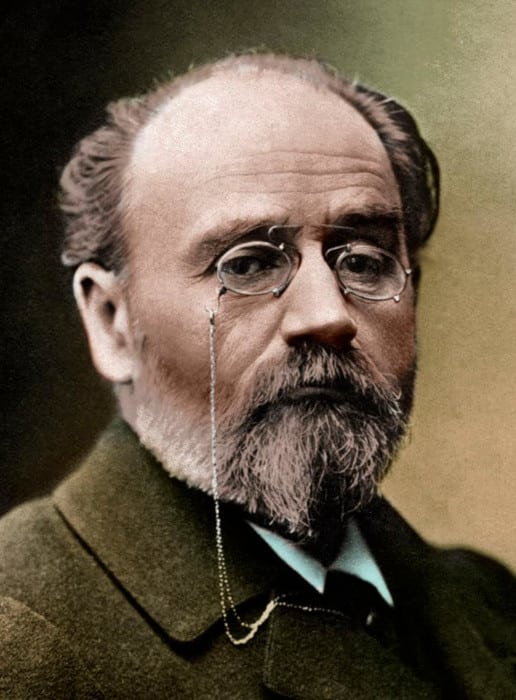

In his youth, Émile Zola was friends with the painter Paul Cézanne. Zola, however, was a photographer, a medium in which the impressions of the artist matter little. This inclination carried over into his writing and is immediately apparent in the best Émile Zola books.

Instead of indulging in impressionism, this author regarded himself as an almost-dispassionate observer of events. In a sense, he’s a scientist or at least a psychologist, placing his characters in situations determined by which hypothesis he happens to be testing and simply noting down their reactions as if they were experimental results.

Best Émile Zola Books

| Photo | Title | Rating | Length | Buy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Germinal | 9.86/10 | 596 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

L'Assommoir | 9.78/10 | 200 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

La Bête Humaine | 9.66/10 | 462 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Au Bonheur des Dames | 9.54/10 | 468 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Nana | 9.50/10 | 432 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

Little Flash, Lots of Substance

As his era’s top naturalist writer, Émile Zola’s books don’t contain the idealized, exaggerated characters you find in Ayn Rand’s or even Ernest Hemingway’s works. Compared to those of his contemporaries like Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac, they’re not even particularly memorable: nobody breaks out in soliloquy or has sudden, world-shaking epiphanies.

“What’s the point of writing about ordinary people doing ordinary things,” you may ask, “don’t we have local newspapers for that?” If you do insist on reading about outlandish heroes doing outlandishly heroic things, well, you’ll always have Nelson DeMille. If you’re willing to dig below the surface of a more realistic narrative for meaning, however, you may be about to start devouring the best novels by Émile Zola one by one.

Germinal

The 13th of 20 Books

The 13th of 20 Books

Widely regarded as the best Émile Zola novel, Germinal is actually part of the Les Rougon-Macquart series, which has more sequels than Star Wars. Many of the mid-19th century settings and themes will be familiar to readers of Charles Dickens, though Zola’s writing style and approach are very different.

Though undoubtedly touching on the politics of a rapidly-changing world, Germinal isn’t really ideological in nature and doesn’t try to offer any solutions to the problems of the early Industrial Revolution. Zola doesn’t dwell on the unfairness of the system. Instead, the fate of the working class is shown only as it affects the protagonist Étienne Lantier, who is first introduced in L’Assommoir. You don’t have to read all of these novels to figure out what’s going on, though, as each can stand on its own.

A True Gem

The plot of this book is pretty bleak at times, with plenty of squalor and conflict to be found against the backdrop of a miners’ strike. Though Zola is unflinching in his descriptions of misery and injustice, Germinal also manages to strike a hopeful note: the situation sucks, sure, and it’s certainly not guaranteed to improve, but there is still room for human qualities like hope and kindness.

However, it’s really the descriptive prose, not the juxtaposition of good and bad, that makes this Émile Zola’s best book. Instead of a sweeping condemnation of the evils of unbridled Capitalism, he presents the story through a tapestry of vivid, everyday details. This novel manages to draw in the reader completely within only the first dozen pages or so, and doesn’t let go until you’ve reached the final paragraph.

L’Assommoir

The Dark Side of Paris

The Dark Side of Paris

L’Assommoir quickly became a bestseller, probably due at least partly due to the controversy it stirred up among the higher classes of French society. Zola went to a great deal of effort to portray the Parisian poor as accurately as possible, saturating the dialogue with contemporary slang phrases (which may or may not come through accurately in translation a century and a half later).

A few curse words weren’t all that brought this Émile Zola book bad reviews when it was published, though. The author simply believed in portraying characters and events as they are, not as we’d like them to be. In the case of the urban poor of his time, this meant discussing promiscuous sex, domestic violence, and alcoholism (L’Assommoir is a cheap tavern).

Humanity, Beautiful and Flawed

All of the best Émile Zola novels strike a balance between optimism and despair, beauty and repulsion, kindness and cruelty. You can expect nothing less from L’Assommoir.

You won’t find any cut-and-paste morality in these pages, though some of the characters are highly sympathetic. Things don’t work out for them just because they’re pure of heart, though, and their deterioration only continues with future generations in the Les Rougon-Macquart cycle, particularly in the novel Nana.

La Bête Humaine

The Human Beast

The Human Beast

While Étienne Lantier (the protagonist of Germinal) is a basically decent though imperfect human being, his brother Jacques is dominated by a dark side. In modern terms, he’s a budding serial killer.

He’s not guilty of the murder which this thriller revolves around, though, but the only witness. Nor is he the (only) bad guy: he and everyone around him seem to be fighting their own private, internal struggles against impulses involving sex, jealousy, and violence. Naturally, some of them lose the battle, leading to a complicated and fascinating series of events.

Ahead of Its Time

La Bête Humaine is way more than a simple detective novel populated by stock-standard characters. The level of action and suspense is certainly on a par with Murder on the Orient Express, though Agatha Christie is of course less on the nose when it comes to violence and sex.

It is the complex and deeply insightful characterization that makes this one of the best books by Émile Zola. What’s equally remarkable is that Sigmund Freud was barely known in France at the time it was written, much less his “death drive” concept which could be said to make up the premise of this book.

Au Bonheur des Dames

Out with the Old, in with the New

Out with the Old, in with the New

Translated as The Ladies’ Paradise, this book also falls under the Les Rougon-Macquart umbrella, though you should have no trouble figuring out its what and who without having read the ten preceding novels. Like the previous three Émile Zola books we’ve ranked, it’s set against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution uprooting livelihoods and old certainties.

In this book, though, we’re not taken to a Parisian slum or a small coal mining village. The protagonist’s job in the new-fangled department store of the title is at least a little genteel, and Capitalism’s effect on the people involved, while still pervasive, isn’t all negative.

Walmart, But in 1882

I wouldn’t ordinarily be all that interested in descriptions of a long-gone store’s day-to-day business and working conditions, but Zola and his incomparable eye for detail manage to make these compelling. These are only important for the impact they have on the characters, though.

For the first time, young women could be financially independent and even attain a certain social standing without marrying. Unlike many authors of his own (and even the modern) era, Zola writes female characters as complete persons. The protagonist, for instance, isn’t blessed with good looks, but instead integrity and a strong work ethic. Martin Amis should have taken notes.

Nana

Femme Fatale

Femme Fatale

A major theme in all of the Les Rougon-Macquart novels is how family and upbringing end up determining a person’s character and lot in life. First seen in L’Assommoir, the protagonist is hardly destined for greatness, having run away from her abusive, dysfunctional family and turned to prostitution.

As Nana opens, however, she’s a rising star in the theater. Her earlier experiences have taken their toll, though: she uses her sex appeal as a weapon, causing one tragedy after another. It’s hard to like her ambition and indifference to others, yet the reader can’t help but see her as a lifelong victim.

Hidden Depths

Of course, as in all of the most popular Émile Zola books, Nana isn’t simply a two-dimensional caricature. Though she despises some of her numerous lovers, for instance, she cares deeply for others. Many critics have accused Zola of writing shallow characters – this is very unfair in my view.

Every reader should remember, however, that this author is first and foremost a naturalist and realist. He doesn’t “tell”, he “shows”, so it’s up to you to keep up. He also treats all of his characters as individuals. If you insist on seeing Nana as an archetype for all of womanhood, you’re going to neither understand nor enjoy this novel.

Thérèse Raquin

A Dark Morality Tale

A Dark Morality Tale

This novel is not actually part of the mammoth Les Rougon-Macquart cycle, but clearly demonstrates that many of the ideas that characterize Émile Zola’s best books were already fully formed at the ripe old age of 27. One of these is determinism (though not entirely in the philosophical sense): given who a person is, which is largely a result of their prior experiences, you can pretty much predict what they’ll do in any given circumstances.

In Thérèse Raquin, this involves a woman and her lover choosing to kill her husband so that she can escape an unsatisfying marriage. Most of this book consists of a clinical, harsh, uncompromising look at the personalities of the murderers (and the guilt they feel after the fact).

Grim Reading

You don’t, generally, pick up one of Émile Zola’s books in order to enter a happy world full of puppies and rainbows. In Thérèse Raquin, however, he seems to go out of his way to make the reader miserable. This isn’t just to be cruel, though: the novel is after all a study of how “human brutes” can be led by their impulses without being free of their consciences afterward.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that this book, like much of the Émile Zola book list, was written so it could be published piece by piece in newspapers and magazines. The same is true for a lot of Charles Dickens and other contemporary literature: Zola may be regarded as highbrow today, but back in his own time he basically wrote for anyone who had a few sous to spare.

L’Œuvre (The Masterpiece)

A Portrait of Artists

A Portrait of Artists

Zola’s fellow naturalist writer Henry James liked to compare the act of writing a novel to that of painting: combining a thousand tiny details into one coherent and compelling picture. The mid-19th-century Parisian art scene, which included poets, painters, sculptors, and novelists like the author itself, was certainly a vibrant and interesting one. There are worse ways of trying to understand it than reading L’Œuvre (The Masterpiece).

This is perhaps the best Émile Zola book in the sense that he truly experienced the atmosphere involved himself, unlike with Germinal and Nana. The main character seems to be based on several famous painters Zola knew himself, including his childhood friend Paul Cézanne.

Drawn from Life

Claude Lantier is the brother of Étienne (hero of Germinal) and Jacques (La Bȇte Humaine) – this book is another installment in the Les Rougon-Macquart series of novels. He’s a talented and innovative painter, but his unorthodox style isn’t what an increasingly commercialized and cliquey art world wants.

Both Zola and Cézanne suffered their fair share of criticism and failure. In this book, these are presented as an integral and perhaps even necessary part of the creative process, at least when greatness is the goal. The artists portrayed in this book persist until the end regardless, drawn to their art like moths to a flame.

Le Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris)

Beautifully Descriptive

Beautifully Descriptive

The writing in The Belly of Paris is noticeably less mature than that found in Zola’s later works like Au Bonheur des Dames, though the greater part of his genius is already clearly discernible. Like most of his novels, the world his characters inhabit is changing rapidly. This is seen, at first glance, in the modern architecture of Les Halles, Paris’ central market.

The recently revamped building is the least of it, though. The rich and bourgeoisie of 1855 (or thereabouts) have access to an unprecedented range of goods, including the food sold in the market and described in delectable detail. The poor, meanwhile, are struggling to scrape by, while political discontent and turmoil simmer just beneath the surface.

Intrigue, Gluttony, and Human Nature

If all high school history books were written like Le Ventre de Paris, the voting age could be lowered to 15. Although this is one of his earlier works, the author manages to sketch an entire scene or era in just a few paragraphs, just like in all the best-rated Émile Zola books. He truly had a gift for selecting exactly the right details to set a stage, relating them without resorting to any flights of fancy yet telling his readers exactly what they need to know.

These sensual descriptions are counterbalanced by similarly realistic yet powerful characterization. In a sense, this book is about the clash between the human and the material, but both of these aspects are given their due.

La Fortune des Rougon

Start at the Beginning

Start at the Beginning

The Fortune of the Rougons is the very first novel in the cycle that finally finds its conclusion in Le Docteur Pascal, Émile Zola’s last book as well as the one that ties together all of Zola’s theories on “heredity”. Remarkably, the author had the entire series sketched out at 28 years of age, before he’d even finished writing this book.

He not only knew the rough outline of the story, but had decided how he was going to approach it and what he wished to say. Aside from emphasizing the role of family and upbringing in a person’s character and actions, this meant showcasing the hedonism and materialism that lead to so many of the tragedies in the Les Rougon-Macquart saga.

Ambition and Idealism

As usual, politics aren’t far from Zola’s mind. This novel is set around 1851 and Napoleon III’s coup d‘état and the abolition of the French Republic. Turbulent times offer great opportunities, of course – for those willing to embrace them.

Not many people have the time or patience to take on the whole of the cycle that defines Zola’s work and philosophy. Actually learning French is probably easier and more rewarding. If you really like this author’s somewhat cynical outlook and exceptional prose, though, and you feel that it will be worth it to learn where the Rougon and Macquart families’ roots truly, lie, La Fortune des Rougon is indeed a natural starting point as well as a great novel in its own right.

La Curée (The Kill)

Much More than a Rerun

Much More than a Rerun

The Kill follows directly on events in La Fortune des Rougon. Though it doesn’t show the author at his full brilliance, it remains one of the best-selling Émile Zola books.

New fortunes have recently been made, but it turns out that trickle-down economics works as poorly in 19th-century France as it does in 21st-century America. The nouveau riche flaunt their wealth and seek new ways to amuse themselves while scrabbling for political power. Meanwhile, a new kind of capitalist – the property speculator – appears, devouring the guts of Paris like hunting dogs eat the entrails of the prey immediately after “the kill” referred to in the title.

Relevant Even Today

When do opportunism and ambition creep over into vulgar, predatory materialism? In what ways do those who desire wealth above all else end up suffering? Are those who’ve always had money without having to work crippled in one sense or another?

This book encourages the reader to think about these questions. As usual, Zola’s unaffected yet poetical descriptions draw you in from the very first chapter. Characters are fleshed out in much the same way – it’s highly likely that you’ll recognize a few people from your own life, just translated into another time and place.

Final Thoughts

More than one reader has complained that Zola takes too much pleasure in glorifying the corrupt and amoral parts of human nature. In his own era, the amount of sex in his books caused particular outrage. Modern readers won’t find too much to be offended by in this regard, but many of Zola’s characters really are appalling and depressing to read about.

However, to quote the man himself “A society is only strong when it places the truth in the full light of the sun.” There may be good in everyone, but it would be foolish to ignore the darker parts of human nature. Zola’s works force us to confront these unflinchingly, yet his books are far from unpalatable, thanks especially to this author’s unique gift for realistic yet insightful description.

Michael Englert

Michael is a graduate of cultural studies and history. He enjoys a good bottle of wine and (surprise, surprise) reading. As a small-town librarian, he is currently relishing the silence and peaceful atmosphere that is prevailing.