Classically Educated Yet Forward-Thinking

Classically Educated Yet Forward-Thinking

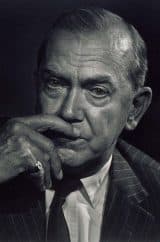

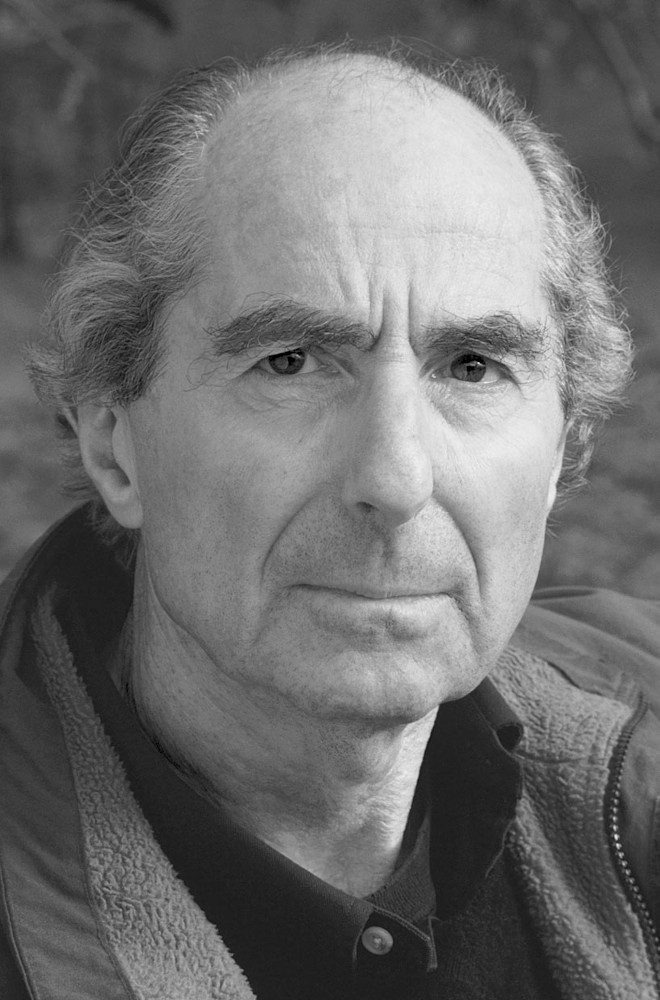

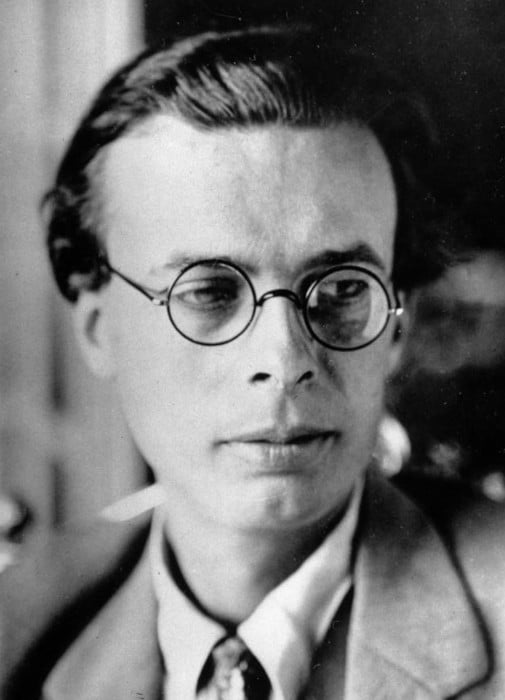

Aldous Huxley was a product of the British upper-class school system just prior to the First World War. As such, he received a broad education: at that time, children weren’t trained for a particular career but rather expected to be able to hold their own in conversations on a variety of subjects.

Both his parents were educators, while other close family members were scientists, philosophers, artists, writers, and senior civil servants. It was therefore no surprise that he grew up to be interested in nearly everything: medicine as well as poetry, religion as well as politics.

Best Aldous Huxley Books

| Photo | Title | Rating | Length | Buy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brave New World | 9.92/10 | 288 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Brave New World Revisited | 9.86/10 | 146 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

The Doors of Perception | 9.76/10 | 187 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Island | 9.68/10 | 384 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

|

Point Counter Point | 9.62/10 | 432 Pages | Check Price On Amazon |

Enormously Influential

How many newspaper headlines have you seen that include the words: “A Brave New Something-or-Other”? Even those who can’t claim to have read the best Aldous Huxley novel recognize the phrase instantly. Similarly, Jim Morrison’s The Doors was named after The Doors of Perception.

Even though his stances on pacifism, technology, and religion irritated many of his contemporaries, his opinions were always sought after. He was a popular public speaker and knew many of the American and British figures who continue to shape intellectual debate today. Basically, you can’t think of yourself as smart unless you’ve read at least a few of this author’s works. In case you’re looking for a starting point, here are ten of the greatest Aldous Huxley books, ranked by popularity:

Brave New World

A Warning for the Future

A Warning for the Future

Brave New World is often mentioned in the same breath as the equally dystopian 1984 (as it happens, George Orwell/Eric Blair was actually a student in Huxley’s French class at one point). Unlike the world of 1984, though, the brave new world Huxley describes isn’t tyrannical and terrifying, but rather grotesquely insipid.

Instead of blatant propaganda and strong-arm tactics, the government keeps its citizens docile through a mixture of sex, drugs, and psychological conditioning. The end result is much the same, though: the whole of society is organized around the principle of conformity. Anyone who doesn’t fit in can be exiled not only from their caste but from civilization itself.

The Opposite of Naive

This book easily tops the list of best Aldous Huxley novels (by sales numbers, anyway). Many of the ideas expressed remain relevant even today: excessive government interference in people’s private lives, technology as a tool of social control, and major issues being drowned in a tide of shallow entertainment.

To place this book in context, it was written in 1932. Prior to the First World War and the Great Depression which followed, most people automatically embraced the Victorian idea that social, scientific, and economic progress was inevitable and inherently good for everybody. After a couple of world-encompassing disasters, some intellectuals began to question this way of thinking: in Brave New World, the future is not your friend.

Brave New World Revisited

Hypothesis and Observation

Hypothesis and Observation

If Brave New World has a flaw, it’s that it’s too didactic. Like many of the best novels by Aldous Huxley, it’s meant to examine and promote a certain point of view, not tell a story. The contrast between primitive and “Utopian” lifestyles is too stark, the debasement of popular religion too complete, and the social interactions of the characters too dismal to be entirely credible.

Brave New World Revisited was published about three decades after the original novel rapidly became one of the best-rated Aldous Huxley books. Plenty had changed in the intervening period: yet another catastrophic war had burned its way through Europe and much of the rest of the world, geopolitical rivalry was threatening to destroy what was left in a nuclear cataclysm, the end of colonialism had resulted in numerous (and mostly unsuccessful) political experiments, global overpopulation was no longer a threat but a fact, and an explosion of new ideologies was turning old certainties on their heads.

Additional, Not Second, Thoughts

This non-fiction essay serves as a kind of review of how far the world had descended into Brave New territory since Huxley’s initial predictions. Overall, he’s not optimistic about our prospects for avoiding exactly those traps.

Brave New World Revisited is more nuanced, though. Spirituality is given much greater emphasis and, instead of a monolithic government, large companies, the media, and several other kinds of organizations are presented as those with hands on the levers of control. With the original novel, each reader is free to interpret it in whatever way they wish, including seeing the World State as the outcome we should be working towards. Revisted is much more on the nose but equally thought-provoking.

The Doors of Perception

Psychedelic Pioneer

Psychedelic Pioneer

The Hippie and other radical social movements of the 1960s didn’t suddenly come into being one day when a student got stoned and started strumming a guitar. Ideas like feminism, sexual liberation, mysticism, and altered states had been examined and promulgated long before, including by Huxley and several of his friends.

The Doors of Perception is nothing more than the author’s account of a single experience with mescaline, a hallucinogen similar to LSD. This was undertaken under the care of a psychiatrist who’d previously done research on the drug. (Though Huxley took mind-altering substances several times during his life, including on his deathbed, he was never a habitual or recreational drug user.)

Chronicle of an Experiment

As a holistic thinker who was deeply interested in mysticism, Huxley had already tried mental exercises such as meditation but had been disappointed with the results. He theorized, based on his practice of Vedanta Hinduism, that the human brain and mind tended to restrict the totality of experience, throttling down our consciousness in both the intellectual and spiritual senses.

It’s not hard to see why The Doors of Perception is one of the best-selling Aldous Huxley books. The author was clearly a genius and, aided by his wife, the observing doctor, a few friends, and recordings of the event, manages to reconstruct the trip in vivid, thoughtful detail. His insights into art and creativity are certainly worth reading and reflecting on.

Some of his ideas on using psychotropics to expand consciousness and explore spirituality are further elaborated in Heaven and Hell, published a few years later. Huxley himself was fairly lukewarm in his endorsement of drugs as a shortcut to enlightenment, though. If you want to read a book about intoxication as such, anything by Hunter S. Thompson may be more like what you’re looking for.

Island

Part of a Greater Whole

Part of a Greater Whole

This author’s last book, Island, in a sense makes up the final installment in the Aldous Huxley book series that also comprises Brave New World and its sequel. Even more so than with Brave New World, the plot of Island isn’t what makes it one of Aldous Huxley’s best books. The action and indeed the characters only serve as a kind of canvas the author’s ideas are sketched on.

Partially inspired by psychedelic experiences like the one described in The Doors of Perception, Island shows a somewhat more human, compassionate touch than Brave New World. Religion, for instance, is barely mentioned in the earlier work except in a satirical sense, yet plays a major role in Island.

Nuanced But Not Subtle

In Brave New World, Huxley draws a sharp distinction between a hyper-modern society and a primitive, natural way of life. In the former, individualism and creativity are at best tolerated, while it’s never clear whether humanity is technology’s master or servant. In the latter, each proposition is almost exactly reversed (within reason).

Island is far more than just a Utopian mirror image of its predecessor, though. The author had clearly learned and grown during the intervening years. Though I personally wouldn’t like to test it out myself, the model he sets out for a perfect society is rooted in non-mainstream but clearly articulated political, psychological, and economic theories. Perhaps more importantly, unlike Brave New World and its follow-up, Island ends on a hopeful note.

Point Counter Point

Write What You Know

Write What You Know

The 1920s and 30s were a seminal period in British intellectual life. It could even be said that these decades mark the watershed between the stratified, hidebound society we find described in the books of George Eliot and the confusing, fast-paced world of Martin Amis’ novels.

Both as a budding writer and through happy accident, Huxley came to know many of the leading intellectuals of the time. These include Bertrand Russell, Alfred Whitehead, Oswald Mosly, and D. H. Lawrence. Several characters in Point Counter Point, arguably the best Aldous Huxley book aside from Brave New World, are based on these figures and hence reflect the current of thought in that time and place.

A Complicated Symphony

As the title implies, Point Counter Point makes liberal use of musical metaphors. Multiple, parallel situations are often presented as variations on the same theme in a kind of fugue; at other times, opposites are contrasted as if to build up a more complex harmony.

This results in multiple, interwoven plot lines. Characters are rich and complex, and it sometimes seems like every other page introduces a new, profound idea that begs to be explored in subsequent chapters. Point Counter Point is one of the longest of the top Aldous Huxley books, as well as one of the more difficult to read. Even so, as an examination of human nature and the challenges thinking individuals face in the modern world (yes, it has certainly remained relevant), it’s hard to find a better novel.

The Perennial Philosophy

Weaving Together the Strands of Spirituality

Weaving Together the Strands of Spirituality

Organized religion didn’t play a major part in the life of broadly educated freethinker Aldous Huxley. He was, however, keenly interested in spirituality: the human drive to fulfillment which is not easily explained by materialistic psychology.

He recognized the universal nature of this personal ambition. Moreover, he also identified a broad base of commonality in all systematic approaches to it. The metaphysical may be intangible and – at least to some extent – subjective, but certain concepts, practices, and ideas crop up again and again in different religious traditions. This is the basis of The Perennial Philosophy: how different theologies, however divergent superficially, all manage to agree on the truly important stuff.

Mandatory Reading for All Casual Philosophers

Published almost immediately after the Second World War, Huxley’s pacifism (which, in fact, prevented him from obtaining citizenship in the United States, where he lived from 1937 to his death in 1963) struck a chord in many readers. The Perennial Philosophy was also one of the first books to introduce Eastern religion and mysticism to an everyday audience. It is especially successful in casting Taoism, Buddhism, and other Oriental traditions as complementary to the Christianity most of his readers would have been familiar with.

Following a particular religion, or none at all, will not detract from the experience of reading The Perennial Philosophy. It is not only one of the best books by Aldous Huxley but a standard introductory text to comparative religion. It’s not academic in tone, though: from Huxley’s own musings on morality and the nature of the spiritual experience to the practical exercises at the end of the book, it’s both inspiring and down to earth without cheapening its source material.

Eyeless in Gaza

An Ode to Peace

An Ode to Peace

Published directly after Brave New World, though not directly linked to it thematically, Eyeless in Gaza tracks the adventures and self-realization of a young man who may well have been Aldous Huxley himself had he not been nearly blind. (The title, however, is taken from a poem about the Biblical Samson by John Milton.)

Disillusioned by the bland and hollow values prevalent among his social class, he tries to find meaning in romance, in commitment to a cause, and finally spirituality. Even as he struggles down the path to a sense of fulfillment, however, he’s haunted by the memory and influences of his past.

Many Things to Like

Unlike in most of Huxley’s earlier and later works, the story is told out of chronological order and makes extensive use of the narrator’s internal voice. The plot is somewhat more interesting than those of many of his other novels, but, like many of the best Aldous Huxley books, Eyeless in Gaza is really a book for thinkers written by one of the most profound intellectuals and students of human nature ever to write in English.

The real heroes within these pages are not the people but the ideas that are scrutinized; the characters are to some extent only vehicles for these ideas. This doesn’t mean that they fall flat, though: Huxley had a true talent for embedding philosophy into a narrative without short-changing either. The main flaw (if you can call it that) is that this novel can be difficult to follow due to the nonlinear story and frequent digressions. There are easier books to keep you busy during your coffee breaks.

The Devils of Loudun

Based on Real Events

Based on Real Events

The Devils of Loudun is often overlooked, lost in the crowd among the most popular Aldous Huxley books. This does not diminish its status as a masterpiece in any way, though.

As a period novel based on real but still poorly understood events, this is kind of a unique entry on the Aldous Huxley book list. Revolving around ecclesiastical politics, petty jealousy, forbidden desires, and mass hysteria, just about the only thing missing from this scandalous tale is the actual devils from the title.

More than a Compelling Story

In the hands of a less cerebral and self-aware writer, The Devils of Loudun would almost certainly have ended up as a psychological or even supernatural thriller with plenty of twists but little depth. Huxley, instead, uses the historical events as a means for examining fundamental questions regarding faith, the existence of the metaphysical world, and the nature of a spiritual life.

Another indication of Huxley’s skill is that this book doesn’t devolve into the macabre, even though torture and burning at the stake are major parts of this story. Both the positive and negative sides of human nature are probed equally. Huxley does this with considerable understanding of theology, psychology, and several other branches of knowledge. The end result is almost overwhelming in terms of the amount of information presented, somehow without ever getting in the way of the narrative.

Ape and Essence

A Story Within a Story

A Story Within a Story

When not writing visionary novels or groundbreaking non-fiction, Huxley made his living as a screenwriter in Hollywood. He was, among other projects, responsible for translating novels by Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë into cinematic format.

Ape and Essence is a different kind of screenplay, in the science fiction genre. It’s just as pessimistic as Brave New World but envisions an entirely different outcome from the interplay between technology and human nature. This movie and its context are introduced as two Hollywood executives drive into the desert to meet its author, whose death they haven’t yet been informed of.

The End of the World

New Zealand, having survived a global nuclear war intact, sends an expedition to the remnants of the United States once radiation levels have subsided. They discover a depraved society based on fear and fanaticism, which just happens to have several characteristics in common with our own.

Parts of this book are quite surreal, especially the scenes where humans are represented as baboons, orangutans, and gorillas. Much of the rest is equally overblown – it is satire, after all, and irony always lies just beneath the surface. Ape and Essence works simply as a story: bizarre but also beautifully told by this author at his most lyrical. It’s far more, of course: most people read Aldous Huxley’s books in order to pick his brain on subjects like morality, politics, and the relationship between the individual and the herd. You will find plenty of thoughts on each of these in this book.

The Genius And The Goddess

The Story of an Affair

The Story of an Affair

The protagonist of this novel, John Rivers, is responsible for destroying the marriage between his mentor, a brilliant but socially graceless scientist, and his beautiful, much younger wife. (They are the genius and goddess referred to in the title.) In that sense, he is the bad guy. The actual circumstances surrounding the various characters and their interactions are far more complicated, though.

This book is partly an exploration of the dual nature of man that inspired so much of Hermann Hesse’s work. Nobody is simply either a thinking, idealistic spirit or a hedonistic, sensual brute: we, and all the people who populate this novel, are each and every one a mixture of both qualities.

Love Is Complex

John Rivers was raised to put love, and especially physical love, on a pedestal. This doesn’t quite work out for him as he experiences romantic and sexual desire in the real world. The intellectual, Apollonian scientist who takes him in lives in a world of stark ideas; his wife is ruled by compassion and emotion. In some ways, they’re completely wrong for one another; in others, they each need their spouse as a kind of counterweight.

The Genius and the Goddess is marvelously complex, both psychologically and philosophically, for such a short novel. Many people consider this to be Aldous Huxley’s best book due to its human element: unlike in Brave New World and even Point Counter Point, it’s the personalities rather than the ideas involved that carry this novel. Nevertheless, die-hard Huxley fans will find plenty of food for thought sprinkled throughout the text in the form of the characters’ opinions on philosophy, art, love, death, and life in general

Final Thoughts

This author is best remembered as a political pessimist and cheerleader for LSD. This is highly unfair to his legacy, though, and all Aldous Huxley book reviews that use that image of him as a starting point can be safely ignored.

Instead, we should honor him as a profound thinker who wasn’t afraid to push the envelope. As a natural scholar, he would go to great lengths to find out all there was to know about a topic, then distill his conclusions into highly readable and thought-provoking works. It’s no exaggeration to say that he has few, if any, peers among modern writers, especially those you’ll find on the bestseller lists.

Robert Hazley

Robert is a science fiction and fantasy geek. (He is also the best looking Ereads writer!) Besides reading and writing, he enjoys sports, cosplay, and good food (don't we all?). Currently works as an accountant (would you believe that?)